The Faustian Bargain of Technology

This Week in SLEKE: Issue #13

We’re glad you’re here! If you believe smartphones should assist us in daily life rather than distract us from it, please consider subscribing and sharing our work. Building awareness and momentum is how we create change and a better path forward.

New technology, this kind or any other kind, is a kind of Faustian bargain—it always gives us something important, but it also takes away something that’s important…

These are the words of Neil Postman, one of the most prescient thinkers of the 20th century. Most known for his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death (among other works), Postman borders on prophetic in his critiques of the technologies that now dominate our lives.

To illuminate the idea of a Faustian bargain, Postman has provided us with a few examples. Political debates being one. The Lincoln-Douglas debates represent the traditional idea of what a political debate is. Or was. These events often lasted more than 7 hours. As Postman said, “today, it’s inconceivable that any group of Americans could endure 7 hours of such discourse”. And he said that in the 80’s! Contrast this to today’s political debates, and you see a stark difference. This difference is facilitated by that Faustian bargain just mentioned. The advent and adoption of TV/screens as our primary medium of information exchange.

(The clip below is from a PBS program in the 1980s, called Currents)

So, what has this bargain cost us? Modern political debates, if you can call them that, are now structured in a way that gives candidates small windows of time to respond to questions from a moderator. All this is of course packaged in a primetime TV slot with advertisements mixed in. But it’s nearly impossible to give a sober, honest, or contextually relevant response to a difficult open-ended question in one to two minutes. And so, indirectly, what does this shift in style of debate reward? It rewards theatrics and histrionics. It rewards the one who can tap into the viewer’s perception of confidence. Someone doesn’t need to be knowledgeable so long as they seem knowledgeable. It doesn’t necessarily reward an intelligible response, even. Cheap points abound.

The Faustian bargain of offloading a majority of our information to mediums like television, the internet, and screens, is that the very information we consume is entirely shaped by the way in which it is presented. It is presented in a way that incentivizes the grabbing of attention over the coherence of intelligible information. Or the context and accuracy of said information. The modus operandi of all modern media is to grab the attention of the viewer/user and to do so by any means necessary. As such, we are subject to the whims of enterprise. And without guts and courage by those who are on the supply side of this information enterprise, you can count on them sinking to the level of the perversity baked into the incentive structure. They have a quarterly earnings report and shareholders to answer to, after all. No time to be constrained by the unprofitable nature of virtue.

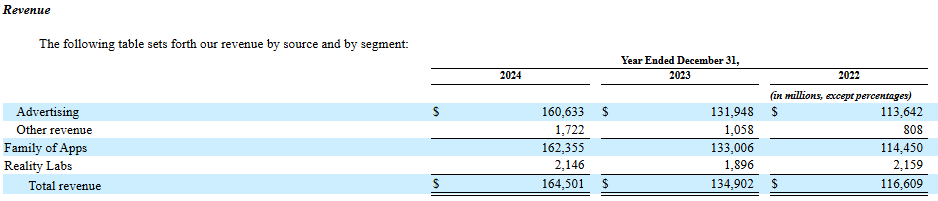

Most of us acutely recognize the fact that we are in a state of informational chaos. That the threads of our attention span are constantly being pulled on by external actors. Modern culture is characterized by a feeling of disorientation around what information to consume and what to ignore. Curating is a part time job. And don’t hold your breath waiting for a mea culpa from those in positions of leadership in technology and media. For the likes of Mark Zuckerberg and Meta, there is a very narrow pathway to profitability. And that pathway is ad revenue. In fiscal year 2024, ~98% of Meta’s revenue came from ads. It totaled around $160 billion.1

Meta is an advertising platform for companies to reach consumers. That’s it. It’s certainly not a place to cultivate healthy relationships with your peers. As a business entity, it will do everything it can to increase your screentime and thus, increase their bottom line.

And while Adam Mosseri, who leads Instagram for Meta, will say things like this, in 2023; “Today, we’re launching Quiet mode on Instagram to help people focus and to encourage people to set boundaries with their friends and followers.”2 You will then hear from Susan Li, CFO, in an earnings call 3 months later; “We have seen a 24% increase in overall time spent on Instagram from our ranking improvements since launching Reels globally.”3 The veil is lifted and we see the only driving force behind the business of Meta. That is, get users to spend as much time on the app as possible.

While we all try to understand what’s happening to our collective attention spans and what to do about it, Meta and other media executives do their best impression of the man in the hot dog suit from I Think You Should Leave. Almost all app-driven media companies operate with a single imperative, which is to increase screentime. They will always be in direct competition with the wellbeing of users. Unless someone wants to argue that more screentime = better mental health…!

It’s a serious problem, but it can help to bring some levity to the situation. It shows the absurdity and helps us realize we can do something about it. That and the analogy is just so spot on.

In looking at our modern technological environment, and our screentime epidemic, we can return to Neil Postman, as he elaborated on the problem of information glut. This from a 1995 interview on PBS’s NewsHour program.

The worst images that come to mind are people who are overloaded with information which they don’t know what to do with, have no sense of what is relevant and what is irrelevant. People who become information junkies.

The problem in the 19th Century, with information, was that we lived in a culture of information scarcity. So humanity addressed that problem with photography and telegraphy. We tried to overcome the limitations of space, time, and form. For about 100 years we worked on this problem and we solved it in a spectacular way.

And now, by solving that problem, we’ve created a new problem that people have never experienced before: information glut, information meaninglessness, information incoherence.

So, how will we deal with this new problem? When Postman said this, I’m not so sure he realized that the smartphone would come along and amplify the problem to the degree that it has. Possibly our most menacing Faustian bargain yet.

What is it that the smartphone in its current form has taken from us? It’s almost a perfect manifestation of a society already veering towards distraction and attention span deterioration. A robust vessel for information glut. An appendage for all of us that provides almost 24/7 access to those on the other end. And as we’ve mentioned before, a seeming requirement to navigate modern infrastructure. As such, we are handcuffed to this tool.

We can once more return to the words of Neil Postman from 1995 to find out what giving us unbridled access to cyberspace (or maybe, giving cyberspace and the actors within it unbridled access to us) might mean. And what might be lost in this bargain…

When I hear people talk about the information superhighway, that it will become possible for people to shop at home, and bank at home, and get your texts at home, and get entertainment at home, I often wonder if this doesn’t signify the end of any community life. When two human beings get together they’re co-present. There is built into it a certain responsibility we have for each other… You can’t just turn off a person. On the internet, you can. And I wonder if this doesn’t diminish that built-in human sense of responsibility we have for each other. Then, also, one wonders about social skills. After all, talking to someone on the internet is a different proposition than being in the same room with someone. Not in terms of responsibility, but in revealing who you are and discovering who the other person is.

In 2025, our community life has diminished. It hasn’t ended, as Postman said, but he was largely right in his worries. We do have less responsibility to each other when we can digitally “turn off a person”. Social skills have deteriorated.

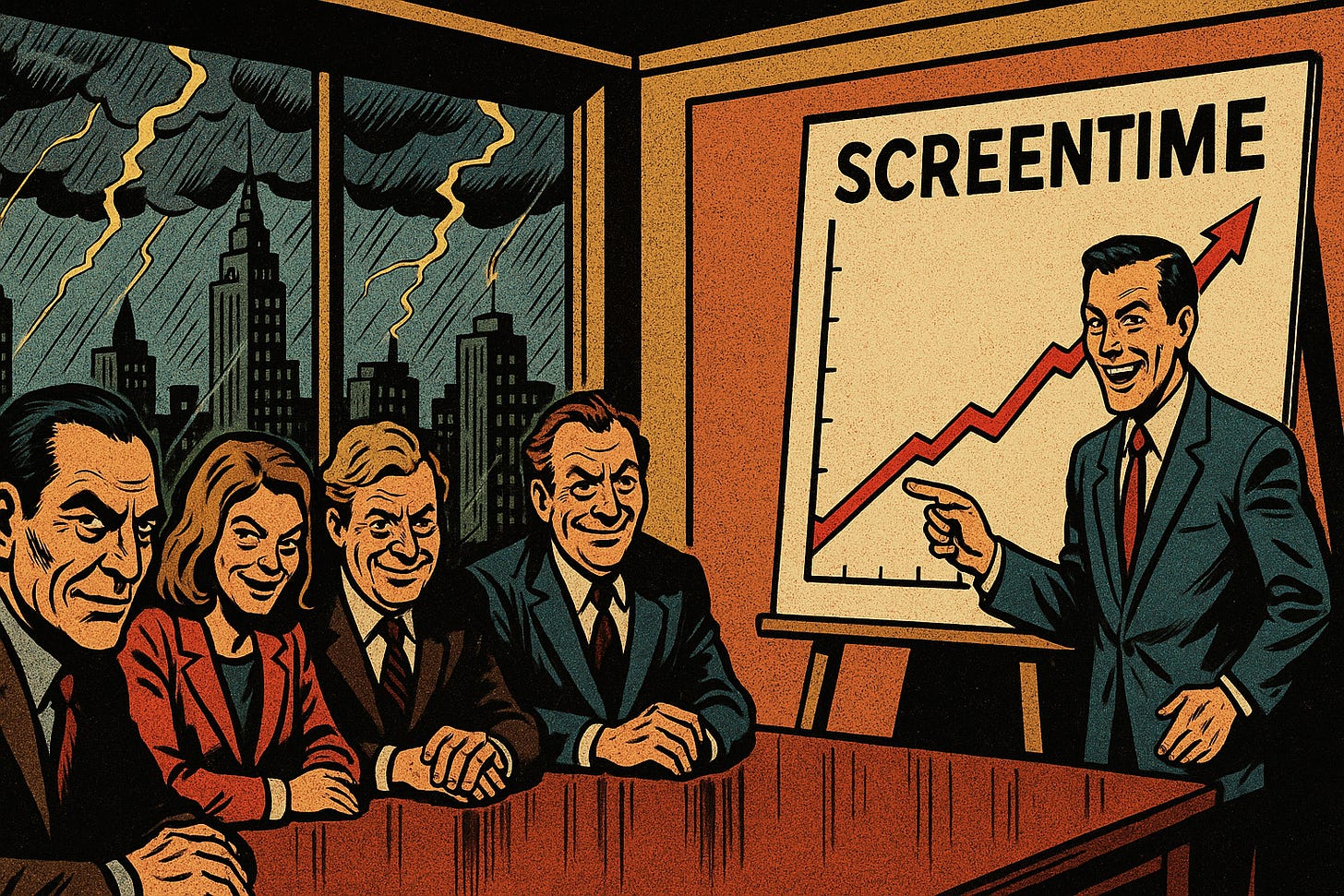

had a phenomenal piece in The Atlantic titled, “The Antisocial Century”. It drives home this reality. Amongst the data, Thompson showed that:In-person socializing plunged by more than 20% since 2003.

Americans spent an additional 99 minutes at home per day compared to 2003.

The share of boys and girls who say they meet up with friends almost daily outside of school declined by nearly 50% since the 1990s, with the sharpest downturn in the 2010s (correlation with smartphone adoption).4

Sure, correlation doesn’t always equal causation, and we can’t say that the smartphone on its own is solely responsible for all of this. But I believe we can say with some confidence that it plays a significant role. Thompson, in his piece, sees phones as one of the primary drivers of the anti-social century.

So what do we do about it all? Well, this is where we at SLEKE are doing our best to make a difference. One thing we keep asking ourselves is how can we use the phone to build community. And to encourage IRL encounters amongst people. We have some ideas for the future and we will continue pursuing a way to make a phone that amplifies our humanity rather than diminishes it. A tall order, but a worthy endeavor. For now, a phone that simply respects the User and doesn’t relentlessly distract and steal their time is a good start. And our internal data is promising, as Users are reporting less than an hour of screentime per day.

We know that we can’t count on current leaders and companies to change their ways. But just as important, we also have to recognize our own culpability and agency in the matter. We don’t have to use Facebook. We don’t have to use TikTok. We don’t have to use Instagram. We don’t have to watch media that traffics in rage bait and theatrics to get a rise out of the viewer. We can seek out thoughtful, sober analysis and information. We can prioritize IRL interactions over digital ones.

But to do so, we need technological tools that respect us. Tools that explicitly operate with a set of values and principles. One might even say, “Thou shalt not exploit the User”.

That’s what we’re trying to bring to the marketplace and accomplish. The solution won’t come from legacy tech and media because the solution is antithetical to their business model. And the solution likely won’t— and maybe shouldn’t— come from government regulation. Shouldn’t in the sense that it would almost certainly be used as a partisan cudgel. Also, because it lets us off the hook as it relates to our responsibility and agency in the matter.

What we can do is create our way out of this problem. Along with other creators, there’s nothing stopping us from building better technological tools. Our friend Amber Case at the Calm Tech Institute has laid out a set of principles for builders to follow. Principles that will lead to a better relationship with our devices.

The crux, then, is whether we can choose to step back from a paradigm that has claimed so much of our time and attention. With it, our emotional wellbeing. This will require both individual choices and creating pathways that make those choices economically viable for creators and consumers alike.

We’re hoping to be a pathfinder in this sense.

Thanks for reading and as always,

Do Cool Stuff

~SLEKE.

https://about.fb.com/news/2023/01/instagram-quiet-mode-manage-your-time-and-focus/

https://www.rev.com/transcripts/meta-platforms-meta-q1-2023-earnings-call-transcript?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2025/02/american-loneliness-personality-politics/681091/

This article is reminding me heavily of the Bo Burnham song Welcome to the Internet. If you haven't heard it, it's worth a listen and sums up our current situation in a chilling, yet amusing way.

https://open.spotify.com/track/3s44Qv8x974tm0ueLexMWN?si=9533b1effd1346f4